With the advent of technology, the suspiciousness of individual representatives of society has only evolved, and for such people there is only one source of truth …

Original material by Dustin Lawrence

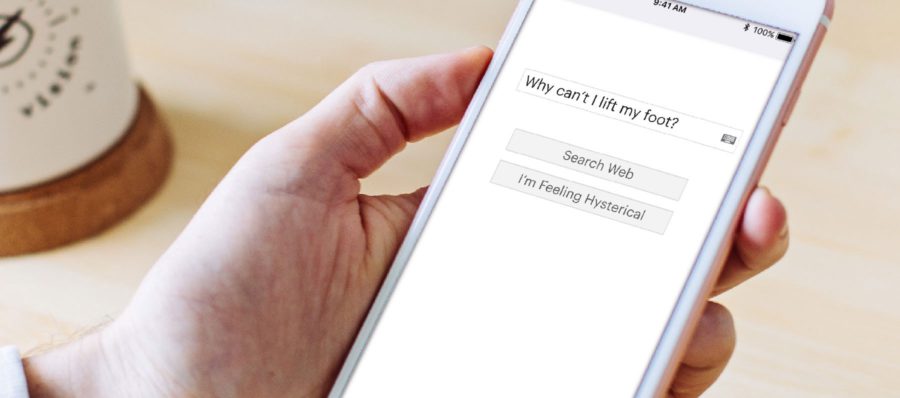

Thursday, 3 AM. I am not sleeping. I can't lift my right leg. Of course, I'm looking for it. 'Why can't I lift my leg?' 20,300,000 results. The consultation continues:

Google: Did you hit your foot?

Me not.

Google: Crushed leg injured?

Me not.

Google: Serious head injury?

Me: Nope.

Google: Neurodegenerative Disorders Leading to Foot Sag.

Me: Oh my God …

Memento mori

From Latin 'remember death'. How can I forget? Reminders of the inevitable with me daily. I am not a philosopher. I'm a hypochondriac. Like many of my eccentric brethren, I often think about my death and the events that will precede it, and one of which, in my opinion, is happening right now. And no matter what anyone tells me, I will not believe them. That is why I turn to the only reliable source of truth – Dr. Google.

Very often, an attack of pain was equated with cancer, and a cut became the onset of necrotizing fasciitis. I have diagnosed myself with diseases that I cannot name, with an emphasis on the worst cases, from the most exotic to the most mysterious, because there is always 'a small chance'. Google 'misdiagnosis' and you will see what I mean.

And of course, maybe technology is making it worse. Mix hypochondria and the world wide web to create 'cyberchondria', a term first coined by The Independent to describe 'overuse of health websites to fuel health concerns.'

I realize that digital self-diagnosis is far from perfect, but why should I pass up this opportunity? A simple search will give a ton of different pathologies to worry about. For example, the WebMD symptom detection app (on all hypochondriac phones, trust me) generates over 50 results for the query 'cough', from the common cold to esophageal cancer. Much the same thing happens when searching for the query 'foot hang'.

All of the above is causing discord in my relationship with my therapist. Here is a quick summary of the previous trick.

Doctor: What are we complaining about?

Me: I think I have multiple sclerosis.

Doctor: Why?

Me: I have a dangling foot – here!

Doctor: Okay, now we'll see.

Me: It's not about the leg, if there is no injury, then certainly multiple sclerosis …

Doctor: Or a pinched nerve in the lower back.

Me: But given my DNA test and what I read on the Internet, the chances of this disease are above average.

Doctor (with a sigh): Well, let's take a look at the lower back first, and I will refer you to physical therapy.

Me: But I need a neurologist!

Doctor: You need a psychiatrist!

You won't be surprised to know that I haven't seen him since. He avoids my calls or is always 'busy with another patient'. I was also referred to doctors who temporarily replaced him, which means that one person cannot be seen twice. This is probably best for all of us.

Usually I look for information on one disease, and in the end two more are added to it. Once I made an appointment because of discomfort in the groin (prostate cancer, of course) and ended up undergoing an examination for a suspicious mole (melanoma), an incomprehensible rash (Lyme borreliosis) and a poorly functioning leg (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).

My name is Dustin and I'm a Google patient

This is the term I prefer to 'cyberchondria', because it more clearly reveals my particular kind of millennial hypochondria. Representatives of this group have the following features and qualities:

- obsessive obsession with information

- thorough knowledge of one's own medical history (and in some cases – DNA sequence)

- a habit of asking too many questions

And according to research in the Harvard Business Review, the solution to our particular problem is quite simple: clarity, order, detailed information during consultation, in brochures and on websites, and transparency about risks and health consequences. This is an urgent need, not least because of the price we pay for cyberchondria. In September 2017, researchers at Imperial College London estimated the cost of travel to a hospital due to internet-driven anxiety at £ 420 million a year, just for outpatients.

Currently, UK medical institutions are not in agreement on how to respond to the situation. The government regulator of therapists, the Royal College of General Practitioners, recently added advice to seeking online before visiting a doctor in its brochure, Three Rules Before Seeing a Doctor, to reduce the likelihood of surgery. Yet hospitals complain that 80% of patients google their symptoms before admission.

The dilemma is real: will rewarding patients to surf the web help relieve pressure on the healthcare system, or will it lead to panic and anxiety among patients?

Looking at the big picture, the cognitive behavioral therapy that the NHS recommends in selected cases of medical anxiety looks overwhelming. In fact, the solution for healthcare professionals must be such that digital diagnostics helps both patients and hospitals by forging strong links between them. Technology should be a platform for dialogue that relieves fear and tension long before a crappy leg causes more worry (and expense) than it was worth.

As the Internet lifts the veil of mystery from medicine and Google's doctor becomes sane, doctors will need to become more human. What about the leg? It turned out to be an inflammation of the tendon.

Original material by Dustin Lawrence

Many of us were in Dustin's shoes: someone was in a fit of worries about the deterioration of health, someone got bored and is trying to find a non-existent reason to worry. For example, quite recently I unwittingly found myself a hostage of such a situation, having googled a cat's weakness, lethargy and lack of appetite. It was scary, but not for long. Cyberchondria is another disease of our time, you can't help it, but it is the easy accessibility of web diagnoses torn from the general picture that scares you. If earlier people had to deliberately invent 'sores' for themselves ('in order to live more fun'), now peace of mind is separated from hysteria and writing a will with just a few words of a search query.

Nevertheless, the scale of the problem led to such discussions, including at the legislative level. Of course, it will not be easy to attribute this to the merits of technology, but there is a silver lining. Don't be like Dustin, don't hesitate to contact the experts. Save your nerves and time, and also you will not invent fantastic scenarios and be treated with a non-contact brain massager.