Based on materials from The Verge

So Android 10 is officially out, but currently only available on a handful of devices: the Pixel lineup and a few other models. No matter how good the new one Android is, no matter how it surpasses its predecessors in terms of data protection, it's no use if you can't get a smartphone for which it is available.

Honestly, I'm tired of resenting the situation with updates Android, which does not change from year to year. We saw the tenth version, and with updates everything is the same as ten years ago: the first in line Google devices are updated quickly, and everyone else has to wait for months or even remain without an update.

However, it would be unfair to say that nothing changes at all. Google has forced manufacturers and carriers to release critical security patches faster. And starting with Android 10, a new initiative called Project Mainline has emerged that will allow individual components Android to be updated directly through the Play Store.

All this is important, but this is not what users want. They want big updates. And yet the ecosystem Android is designed to not allow big updates to reach users. It is a fact. And since nothing has changed in ten years, we are forced to come to a sad conclusion: Google cannot solve the problem. And no one else either.

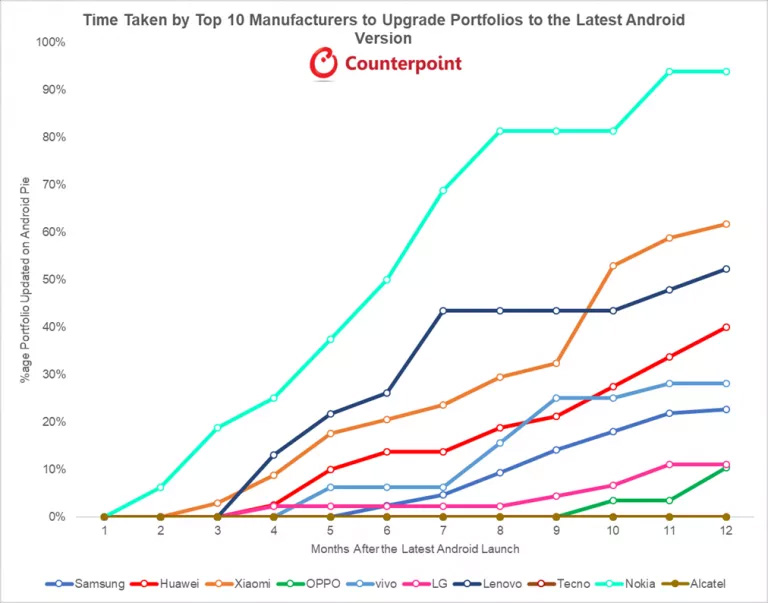

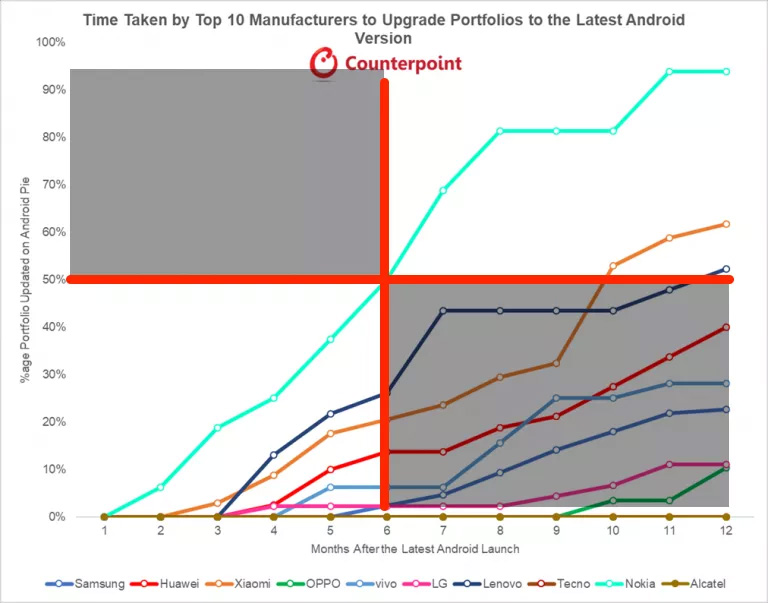

Take a recent report from Counterpoint Research, which points out that Nokia is leading the pack in major updates by a wide margin (after Google and Essential, which have far fewer device models that require support). The report has a representative chart that shows the percentage of Android 9 Pie devices in the company's portfolio in the year after its release.

How Nokia has pulled ahead is striking. But this chart is not about success, but about failure. Let's go over the most important details.

Six months after the release, only one manufacturer was able to update half of the portfolio, and only two more than a quarter. A year after the release, only three manufacturers have crossed the 50% mark! And the two largest and most important manufacturers, Samsung and Huawei, settled on values of about 30 and 40%, respectively.

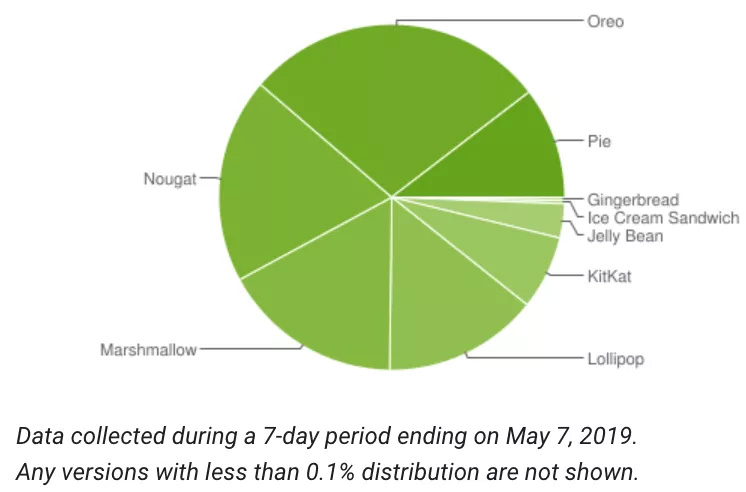

The lion's share of smartphones sold during this period were running the latest version. But very few devices purchased before that have been upgraded to 'nine'. There is a more traditional way of measuring the installation base Android that we can turn to, and it also shows a rather pale picture. This is a custom distribution graph Android:

As of May Android 9 Pie barely broke the 10% mark. Better than in previous years, but no less awful.

You may already be tempted to declare that this is not a problem at all. Google manages to release security updates more often, and many of the features that appear in new versions Android are often already available in skins, such as in Samsung's One UI.

However, let's not forget about one important point. People have started buying smartphones for a longer period of use as prices climb inexorably. Not getting a new version Android a year after purchasing the device is still nothing. But what if it's two or three years? Quite another matter.

What is the reason? How the ecosystem itself works Android. It is an open-source group, nominally independent from Google, and includes all the major players. They can take the kernel Android and do whatever they want with it. Some of them resort to minimal customization, which is easy to transfer from version to version, and some make life difficult for themselves. Sometimes (quite often) the costs for the manufacturer do not pay off, especially for older devices. Finally, operators usually check how updates are working with their networks, which further slows down the process.

This is a simple explanation of why updates Android take forever. A slightly more sophisticated version starts where Android is 'nominally' separated from Google, which effectively means that Google controls Android. She spends a lot more resources on its development and determines which features will be included in which version. The company also controls, or at least very seriously affects the entire ecosystem Android, as it owns the Play Store and creates the most popular applications for Android (Chrome, Gmail, etc.) .

In other words, Google has two levers by which it can push updates Android faster in this fragmented ecosystem. These are technical and political levers.

Let's start with the technical one – Google uses it very actively. We have already mentioned Project Mainline and monthly security patches above. But even more important is the Project Treble. It emerged in 2017 as a multi-year initiative to change the way Android is built, to make it more modular, to make it easier for manufacturers to create add-ons.

Technically speaking, Treble is a lever of pressure. Google dictates how manufacturers use Android on their devices, potentially limiting customization in favor of an early update.

However, two years have passed and one would have expected a more significant effect from Treble. Yes, many companies have started to release updates faster, more of them participate in beta tests Android. But Android is spreading slowly and Treble is not a panacea. It is possible for Google to simply change Android and take full control over the release of updates, but this looks like a utopia.

Political leverage refers to the combination of incentive, persuasion, encouragement, judgment and begging that Google uses to maintain the integrity of the ecosystem Android. And it works, but as with technical leverage, more could be done. You can imagine that Google requires timely updates of devices that have the Google Play Store and Google apps. The company has dealt with such coercion for other purposes before, but it did not end well, causing a confrontation with the European Union, which forced it to give the option of choosing a default browser and remove mandatory applications from the OS package.

Google could make the most of each of these levers, but it doesn't. And it's not about the shyness of the company. The point is that this can cause even more fragmentation. The less compliant and tougher Google becomes with regard to Android and Play Store policies, the more likely a number of companies are to abandon Android, as Amazon did with the Fire tablets. . And it will be a disaster for Google.

It doesn't have to be that way. Microsoft, for example, has created an ecosystem for many manufacturers, but has nonetheless put in more effort in terms of updating Windows Phone. On the other hand, perhaps this was one of the reasons why the company was defeated – manufacturers were much more interested in making phones on Android because they could differentiate (or monetize) their own phones more. .

Even Google itself has managed to tackle this problem, simply in situations where the rates were lower. Wear OS, Chrome OS and Google's smart speaker platform all receive updates directly from Google. Parts of Android such as Android Auto cannot be changed by manufacturers and are updated via the Play Store. And with Android himself, it all went wrong from the very beginning.

Some Google fans may not be very concerned about this, as the current situation gives a big advantage to Pixel smartphones. But the company itself is hardly satisfied with how the updates work Android. She just doesn't know how to put more pressure on her levers.

On the other hand, Google has very gracefully bypassed some carriers by implementing its own RCS messaging. There may be ways to creatively combine politics and technology to solve a problem, but nothing comes to mind, and hardly any of the geniuses out there at Google can boast of it. And if I could, I would have done it already, and we would all happily upgrade to Android 10.

In the end, you can wait for Fuchsia and hope that it will be updated normally.