Contemporary photography is changing the way we remember our lives. Photos posted by us create real-time nostalgia …

Original material

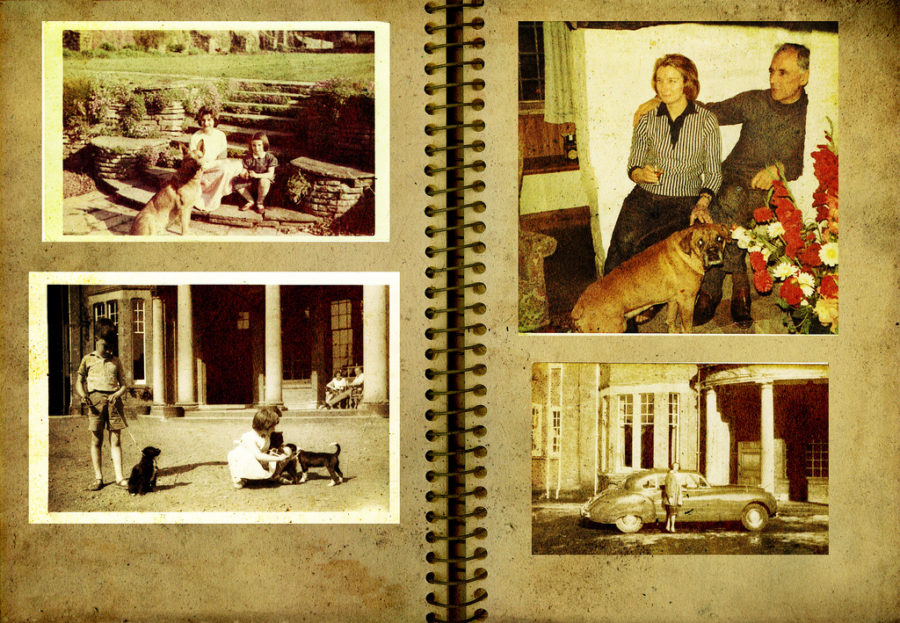

I remember digging like a kid in yellowed Polaroid photographs from a dusty shoe box that I dug up in my grandmother's closet. We sat down on the sofa and started taking out old photographs one by one. Although the grandmother could not remember where and when exactly a particular picture was taken, each of them conjured up its own story in her memory. She brought the photographs to life. As she relived each shot, we cried, laughed, I learned more about her than ever. In the blush of the late evening, I watched Grandma reluctantly shake hands to put the photos back into the box.

Since then, photography has changed a lot. Today the moment has not yet ended, but it was seen by someone many kilometers away, someone whom we may not even know. Our photos are instantly available to the whole world, and our memories are formed in real time.

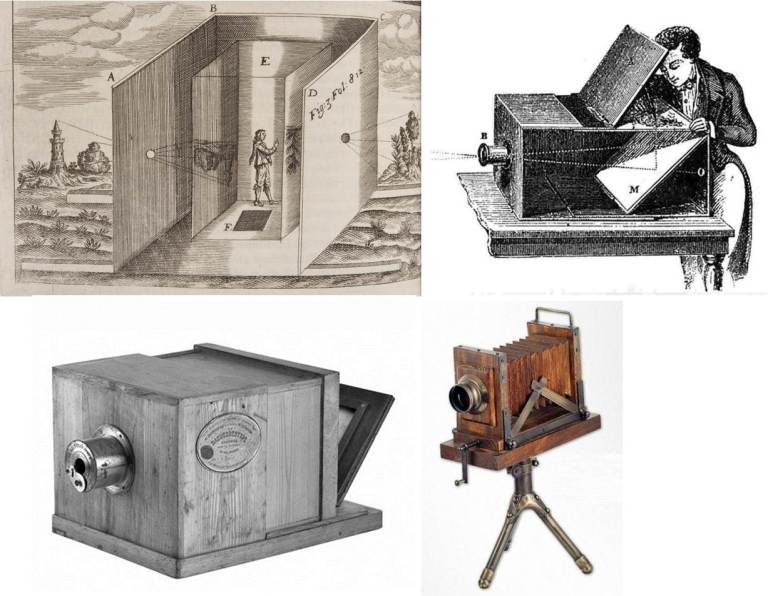

The history of the modern camera is intertwined with our need to create, capture and remember. The camera began redefining nostalgia in 1888 when Kodak released a small and simple personal camera for hobbyists. “You press the button, we do the rest.” The camera quickly became an indispensable tool for recording and carefully selecting moments from our lives. Precious moments turned into memorable albums, and those episodes that we didn't want to remember were forgotten. Film photography was 'shot' in 1999. That year, users around the world took about 80 billion photos.

The ubiquitous smartphones with built-in cameras over the past decade have contributed to more photographs than we have ever taken. In 2017, the number of images approached 1.2 trillion, and more than three billion images are sent daily via social media services.

Few could have predicted that our relationship with photography would become this close. The obsession with documenting our lives even affects how we experience and remember the world. We see more moments through the camera and spend more time on our phones watching the lives of others.

Phone and experience go hand in hand. We travel the world in search of moments worth capturing, which in turn determine how we perceive our environment. Given the number of photos we take, it's no wonder some people are worried that photography gets in the way of 'real life'. Many of us have been told to put our phones away and live in the moment, but there is real scientific backing for that.

Scientists have found that intense social media habits can impair the way we store memory. A 2018 study confirmed that participants were more likely to forget the objects they photographed than the ones they just observed. This phenomenon is known as 'photography impairment' and was discovered and described in 2014. Scientists have also found that memorization through photographs can override other forms of understanding. When we see events taking place in the real world through the camera lens and on our screens, then we absorb only a fraction of the experience. In other words, we are visually involved but deprived of other important sensory information.

Taking photographs can also be a form of cognitive offloading. Being confident that the complex task of recording information is being performed by the device, you unload part of our memory into digital memory. “You also don't have to remember because the camera will do it for you,” says co-author Jennifer Soares, a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “It's like taking a picture of your parking lot number and not even trying to remember it.” Yes, we all did that. But for the most part, we don't take a photo to remember the details. “Some photographers will argue that their photography does not mean cognitive relief,” says Soares, stressing that the statement is relevant to those who view their work as art that has the exact opposite function.

And yet the consequences of this era of dominance of photography are quite unexpected: while photography helps us remember our experience, the number of shots and platforms within which we create them makes it easier to forget them. Photographed, shared, scrolled through, again – the photos became ephemeral, merging and disappearing in an endless stream, mostly unnoticed and extremely rarely viewed again. Thus, photography returned to its very origins.

1290, Arnoldus de Villanove gathered a small group of people in a darkened room. They gathered around a beam of light on the wall, which shows an image that is not quite clear and bright, but enough for scenes of bloodshed in war and then – hunting an animal to appear on the wall as if by magic.

Villanove was a practicing therapist, a showman in his spare time, and a wizard for his audience. The paintings he created were at the same time distant and intimate. The audience drew meaning from each shot before it faded away. After the presentation was over, a small group of people whispered enthusiastically, reflecting on Villanove's skill. But he was not a magician, but rather the progenitor of photographers who worked with a camera obscura. Yet he gave the audience what was probably the first glimpse of future photography.

Think of your parents' collection of baby photos – funny haircuts that have become immortal in shabby photos. The camera turned the subjects of shooting into objects of the future and immediately the past (memories, good and not so good). Photos were taken much less often and in limited quantities. Few were given the chance to choose between many variations of the images captured in a minute. Selected photographs were collected and stored, and until we decided to get rid of them, they were constantly with us.

When it becomes easy to take pictures and easy to share, they lose their meaning. Now we are full of nostalgia for the fact that photography has lost its ability to influence us, we no longer care about most of the photos we scroll through. It has become quite common for social services to use algorithms to help us determine which ones are important.

However, Snapchat is emerging as a new catalyst for the trend of meaningless photos and videos, with users posting fast-disappearing content.

Nathan Jürgenson, author of The Social Photo, wrote in 2013 that ephemeral photography is a cultural response to photographic dominance: “Temporary photography inspires us to remember because it involves the possibility of forgetting.” In other words, photography's allotted 'life cycle' and its fleeting nature change the way it is created and perceived. You create a story at Instagram and it disappears after 24 hours. So the photo is more appreciated, discussed and remembered in a new way.

Jürgenson said he distinguishes between traditional photography (a permanent documentary subject) and social photography, which tends to be 'ephemeral, playful and expressive'. Social photos, such as those posted on Snapchat, “try to capture the experience of the moment as the photographer perceived it.”

Photographers will continue to play the role of witnesses of history, art and helpers for our memory. And yet we increasingly see the world not as something to capture photographs in granite, but as something with which to communicate. If a photograph is as important as its context, then the experience is different and the moments are remembered or forgotten. The pictures I send to my friends today are strangely similar to that nostalgic day at my grandmother's.

But it is likely that this new era of photography will not be similar to the aforementioned performance from the late 13th century. We share and discuss our feelings as we experience. Photos turn into 'stories'. They make us cry and smile. We write, draw on them, apply filters to them. We squeeze meaning out of each image before they disappear, just like the Villanove audience in that dark room.

Author – Stéphane Lavoie

An excellent reflection of the spiral of the development of photography: in some ways the situation repeats itself, but at the same time it acquires the features of a new time, changes, but continues to bring beauty and meaning to the world. Mobile photography plays a double role in this. As the author shows, there is nothing wrong with this, it’s just another round of evolution. In the homes of familiar young families, an album with photographs is rather an exception to the rule, but this does not negate the fact that physical photographs are closer to digital ones.

Did this make our memories more fleeting? Do we strive to be in the public eye all the time, live for show, getting 'likes' from strangers and bots? Or are we just following the lead of the general stream and do not want to get out of sight? Everyone should answer these questions for himself.

P.S.: Imperceptibly, I approached the 200th issue of the Gazebo. I want to thank all readers of this column for their attention, comments, tips and criticism. Nobody is perfect, but I am a reader just like you, so we will develop together. Thank you!