More recently, on April 29, 2019, the Tele2 operator managed to create a stir in the Russian telecommunications environment by starting the sale of so-called electronic SIM cards, or more simply eSIM.

Taking into account the peculiarities of the legal field in Russia, it was necessary to use crutches in the form of an initial connection by purchasing a traditional physical medium – an ordinary SIM card, followed by its re-issuance to the electronic version of eSIM, and the previously purchased physical medium had to be handed over to the operator.

This holiday did not last long, literally the next day after the unexpected start of sales, sales were also suddenly stopped.

The operator explained this with great excitement. However, later there was information that the sale was suspended due to the request of the Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications.

According to a Tele2 representative, it was only a pilot project, not a full-fledged launch. The operator is said to have gained the necessary subscriber base to test the technology and suspended the sale.

At the same time, information from the department contradicts the operator's version – a representative of the Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications said that before making a decision it is necessary to hold additional consultations on the safety of using such technology.

All Russian operators will take part in the discussion of the issue (which previously were actively against the introduction of this technology, fearing costs and financial losses).

But more on that below, and now – a little history.

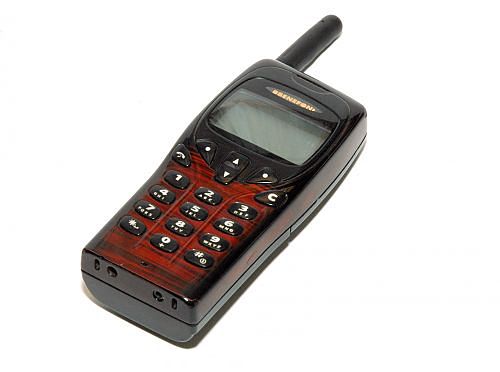

At the dawn of the development of cellular networks, mobile phones (not GSM) did not have SIM cards at all, and the number and all the necessary information were literally soldered into the device itself (later programmed) in the operator's service center.

That is, in order to connect a new device to the network, the owner had to bring it to the operator's office and leave it there for two or three days. Usually, this was exactly what was required for the procedure of inserting the number into the phone. I remember how I myself waited for three days while the number was soldered into my phone.

In addition, the service in most cases was not free. After that, the owner received his phone with a number sewn into it, which could be changed in exactly the same way.

Then, with the advent of the GSM standard, everything became much easier – the usual SIM cards appeared. Well, as usual, the first phones supporting SIM cards had a rather large cutout at the base, into which a SIM card the size of a current bank card was inserted.

This was not a problem exactly until the moment when the devices began to lose dramatically in size, and the entire industry took a course towards miniaturization.

The struggle for the internal space began, and one of the first to sacrifice was the extra plastic of the SIM-card, which became much smaller.

That is why the so-called 'regular' SIM-card familiar to many is actually a mini-SIM-card.

Actually, all subsequent metamorphoses are dictated primarily by a decrease in the size of devices, which means increased requirements for free space inside for electronic components.

This is how Micro-SIM first appeared, and then from the filing Apple and Nano-SIM.

Despite this, the engineers did not abandon the idea of completely getting rid of the physical carrier by making the subscriber ID (which is the SIM card) completely digital.

Thanks to the development of cryptography and the increased computing power, this is not only easy, but very simple. Moreover, in many countries the technology is implemented and used. Among the pioneers of the practical use of this technology are countries such as Austria, Great Britain, Hungary, Germany, India, Canada, Croatia, the Czech Republic and about a dozen other countries, and now, thanks to Tele2, Russia.

However, in Russia, the introduction of this technology has faced active opposition from both the controlling authorities in the person of the FSB, where they prefer to either control everything or simply prohibit what they cannot or cannot control, and from the Big Three operators who saw the introduction of electronic SIM cards are a threat to their traditional business with blackjack … Communication salons and sales consultants.

FSB fears are connected with the impossibility at the moment to apply Russian methods of cryptographic encryption to electronic SIM-cards.

And if the feds with a certain amount of assumptions and 'but' can be understood, their job is to watch and prevent, then the position of accepting this technology with hostility on the part of cellular operators is seen as a banal fear of losing the subscriber base due to the simplification of the procedure for changing the operator and the need to revise some business processes that will simplify the life of an ordinary subscriber and give him more freedom.

Time will show how far-sighted such a position of denial and reinsurance on the part of the Big Three operators will be, however, despite their desire to slow down progress, permission from the Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications to implement the scheme of selling electronic SIM-cards tested by Tele2 has been received, which means that soon it will be possible to test this technology on yourself.

There is little left to do – to prepare a regulatory framework for remote identification of subscribers, which will allow us to get out of the intermediate stage in the form of buying a physical carrier and then exchanging it for an electronic version of a SIM card.

As a result, everything should come down to completely remote registration and downloading a new number to the device in the same way as today we download a package of mobile Internet settings or license keys for software products.

Instead of a conclusion

The question of the need to introduce this technology is not worth it – electronic SIM cards are already needed today, and in the context of the development of the Internet of things and the launch of fifth generation networks, they will become an urgent need.

In addition to increasing human mobility, with the introduction of full-fledged and widespread support for this technology, the problem of an additional slot for a SIM card will cease to exist, as well as the risk of failure of this very SIM card.

The only question is how soon it will happen and what (or who) can get in the way of this process. Do you, dear readers, need this technology?