There is no reason to believe that the digital world is facing death or radical transformation, even if its negative impact becomes more and more obvious … What to do with its negative effects?

Original material by Ian Marcus Corbin

The brake lights in front turned red, and I, without even thinking, put my foot on the brake pedal to the stop and reach for mine iPhone, eagerly moving my finger to the fingerprint scanner, like a baby reaching for a breast. Depending on the length of the inhibit signal, I have from 30 to 90 seconds to quickly scan Facebook, Twitter or Instagram or skim over a couple more paragraphs of the article started before the trip.

I don’t do this at every traffic light, but if I really want to, I’ll get on the phone under any circumstances: night, day, company or loneliness. I will do this because at the moment I am bored, sad, lonely or I am under stress, and it is at such moments that I need likes, words and pictures from you, people, like a thirsty, breathing heavily and crawling through the desert, a traveler needs water.

If the situation were unique, it would hardly be worth writing about it or reading about it. But this thirst is our common one. This idea is confirmed by the drivers around: the eyes seem to be glued to some point below, only occasionally the glance runs appraisingly around the environment. If someone is so keen on viewing that they miss the green light, then drivers who spotted it a second earlier will not fail to use sound signals.

It seems to me that there can be nothing new under the sun, judging by how much of modern human essence is described in the works of Plato, Ecclesiastes or the Lascaux caves. So we sit in these wonders of modern technology, buzzing and burning inside, scrolling through the news feeds like caught and scratching cats in the oppressive silence that people have fought for centuries. In the 17th century, Blaise Pascal said that most of the world's problems arose from a person's inability to sit still in a room. In the 4th century, the monk Evagrius of Pontic, as well as many monks close to him, spoke of a sin whose name is idleness, unreasonable restlessness, a quiet intense fear that this place and this essence are bad, and good awaits us somewhere out there, all that remains is to take it all. Therefore, we rush about within our minds in an attempt to touch the best in our own way. Evagrius Ponticus wrote: 'The demon of idleness – known as the noon demon – is the most problematic. He makes the sun seem motionless in the sky, and instills in the heart of the monk hatred for his environment and his very life. '

So this place, this time, this essence is not enough for us. Functionally, they are quite good for themselves, but for some reason they have died out, have lost the wealth of life to which we strive. All I have now is a car with ordinary black seats, a boring smooth steering wheel and an unremarkable ability to move in space. All this is invisible to me and does not help me in any way to get closer to those things that I really want / need. So I mentally run to better places, at least brighter ones.

It is not easy to unravel the tangle of depravity and benefactors, probably not for paper. Strict self-control can easily and imperceptibly turn into contempt for the weak and lazy, and honesty into tactlessness. If people were not overwhelmed by dissatisfaction, did not look down on their current state, then we would have available fewer examples of human genius, fewer skyscrapers, novels, cars or iPhone. This is the important thing that divides us, makes us conquerors and builders, makes us better or worse. Worse because, above all, this thirst for the unavailable makes us unhappy, detached and alienated from people and things around, including the great monuments that we should admire.

All of this is nothing entirely new, which is not the case with our ubiquitous electronic escapism tools. Like all forms of human interaction, sharing online can be fun: a photograph of a child, a reassuring article, or a poem or song. But in our worst moments of 'thirst', we usually take our time to visit our digital friends out of an excess of joy or a desire to share their joy. It's not even just stimulation. At this very intersection there are many things that I can pay attention to: cars, drivers, trees, grass, birds, pedestrians, music on the radio. But we need something sharper, more urgent.

When someone writes a post on a social network or an article, then one seems to be preparing for battle. I want to write more poignantly, or more musically, or more comprehensively than others. You want to look prettier, happier, or more fortunate than the people who are looking at your photo. We want to evoke feelings of envy, respect, or even lust. All these desires are quite natural, they position us against the background of our digital friends in this endless crush in the struggle for status and recognition. We look at pictures of our 'friends', read their words, partly to understand what they are capable of. We may wish them happiness and success, or we may feel a little positive emotion as we celebrate the fact that our lives are better.

A recent study found that the average phone user “engages in 76 complete phone calls a day, with an average of 2,617 phone touches.”

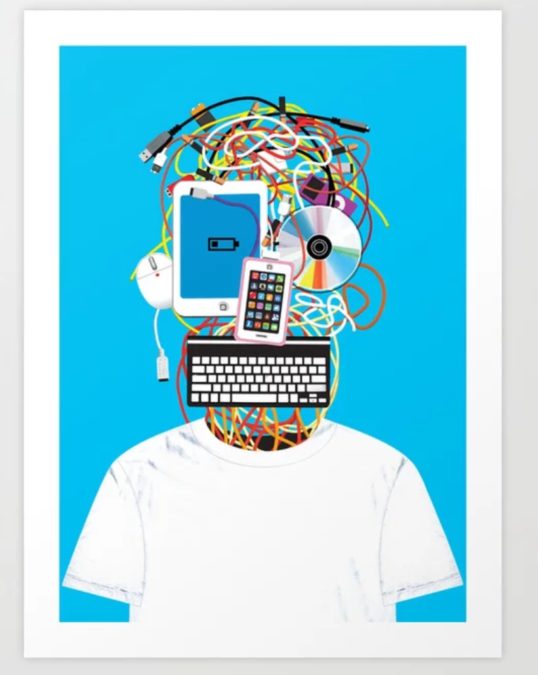

In short, your phone, this soulless box with microcircuits and wires, available to you around the clock, seven days a week, brightly and sharply focuses attention on the big arena of competition between people and on the bright, loud emotions that accompany it. A happy person may well be content with contemplating the view from the window. A sad and restless person needs a stronger 'medicine' and will strive to get it, even if for this it is necessary to rashly and stupidly glance at the phone while driving at a speed of 100 km / h. Thousands of genius minds today work incredible hours for a good salary and their share of social prestige. They apply disruptive science by which the phones we buy and the apps we download pull us in and keep us coming back to them.

Undoubtedly, everyone knows that things like social media are not useful for us, that many of us are clinically addicted to phones, that online life awakens a negative side of them in most people. The news usually comes out like this: someone said something and Twitter is filled with indignation, and the details come later. Here's the news for you. We react to this with a know-it-all grimace, we write sarcastic tweets about the toxicity of the service. We admire the creators of websites and apps that make us unhappy, and with ambition and entrepreneurial spirit, we want to be just like them.

The trends of time change smoothly, except until that time, until there is a lightning coup. People are weak and will quench their thirst with the first liquid they come across, at least for the first time. There is no reason to believe that the digital world will face death or radical transformation, even if its negative impact is becoming more evident. I believe that technology and especially the use of social media – this gigantic monument to our collective creation – will begin to be perceived as a social disease within the next ten years. Research is piling up, and this harm is perhaps the most obvious moral argument to date.

This will be one case in which the advice of doctors can be linked to older and deeper attempts to penetrate human nature. There will be whole social movements around the idea of disconnecting, abandoning the little buzzing and jingling boxes in our pockets. This may be reminiscent of the example of the Wandervogel, a spontaneous movement among groups of German youth who, at the end of the nineteenth century, rebelled against the industrial life of large cities, opposing it to long joint walks in the forest in search of tranquility and human solidarity. Or perhaps we'll be doomed to contemplate a new iteration of the hippie. Who knows what form this movement might take?

The rejection of the digital world will by no means be total, many mass reactions tend to be a pendulum effect. But in 2018, it feels like the whole world has reached its limit. Dostoevsky said that man is the only animal that gets used to everything. And, yes, this may be true. But in the medium and long term, humanity has a rich experience in recognizing inhuman tendencies. Thirst will not go anywhere, but civilization will not be able to drink a lot of salt water.

Original material by Ian Marcus Corbin

A kind of philosophical view on the problem of dependence on gadgets, according to the author, which is not something new, except perhaps for coverage. And although the author himself admits that he is partly 'sick', his reasoning comes to the conclusion that mankind sooner or later realizes the full depth of the problem and begins to massively abandon its 'boxes with wires and microcircuits'.

A funny parallel with hippies and teenagers walking in the woods, really what will these digital hermits be like? Among my environment (including the network) there are individuals who, quite consciously, drop out of online for a day or two a week and live quite well for themselves. By their example, one can quite imagine a society of creative people united by the idea of digital escapism for the benefit of people. Of course, utopia, but who knows where this path will turn.